(Note: this is a long entry, because it’s sort of a meta-post exploring the diversity of creative and critical work that comprises medical humanities, with links to lots of examples. Read it in chunks, if that’s easiest.)

I’ve promised participants in my latest medical humanities seminar that once they understand what medical humanities is, they’ll start to see it all around them. How many films we watch, poems or novels or memoirs we read, works of visual art we see, plays we attend, or songs we hear explore some aspects of illness, or disability, or caretaking, or the end of life, or some other theme that fits within medical humanities? And how many “real life” issues relating to health, health care, and mortality can benefit from the perspectives that philosophy or literature or history or other humanities disciplines offer? Medical humanities gives us a way to understand our most profound and sometimes most challenging experiences.

In fact, I realize now that I was “doing medical humanities” before I ever knew the field existed. Looking back, I see how this work represents some of the breadth of the field: “Factory Girl: Dora the Explorer and the Dirty Secrets of the Global Industrial Economy” is an article I wrote for Bitch magazine in 2008, not long after a slew of toys, many of them Dora the Explorer-licensed merchandise, being sold in the US were found to contain lead paint. In the article, I analyze intersections of popular culture, appropriations of “multiculturalism” by multinational corporations, and public health crises in the global economy. So this work of cultural criticism fits within medical humanities.

“Factory Girl: Dora the Explorer and the Dirty Secrets of the Global Industrial Economy” is an article I wrote for Bitch magazine in 2008, not long after a slew of toys, many of them Dora the Explorer-licensed merchandise, being sold in the US were found to contain lead paint. In the article, I analyze intersections of popular culture, appropriations of “multiculturalism” by multinational corporations, and public health crises in the global economy. So this work of cultural criticism fits within medical humanities.

My poem “The Calling” was published in Cloudbank, a literary magazine, in 2010. This is a creative work about patients and providers in a women’s health clinic, based on my experience working at Planned Parenthood in the early 1990s.

Another of my poems was selected in 2012 to be inscribed on the wall of a hospital, the Kaiser Westside Medical Center, which opened in 2013. This creative work isn’t about patients or practitioners or health or health care. It’s about nature, and was chosen to be part of the hospital design because of research indicating that art contributes to a healing/healthful environment. Years later, a friend told me about when she was undergoing surgery to have cancerous tumors removed at this hospital. Just before the operation, her boyfriend noticed the poem on the wall. They had no idea a work of mine was there, and seeing it helped both of them with the emotions of the day.

My first novel, The Secrets of Mary Bowser, is based on the true story of a woman born into slavery, who was freed and sent North to be educated, but then returned to the South, where, during the Civil War, she becomes a spy for the Union by pretending to be a slave in the Confederate White House. In this creative work, I incorporate details of illness and medicine to transport readers to a particular time and place, writing about yellow fever and smallpox epidemics, and about some of the very first use of vaccinations, which saved lives then just as they do today.

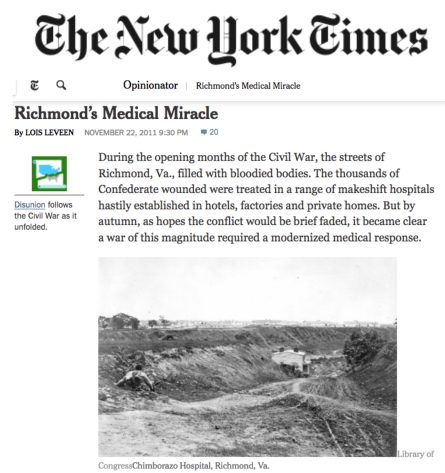

The Secrets of Mary Bowser was published during the sesquicentennial (150th anniversary) of the Civil War, which The New York Times marked with a series entitled “Disunion.” I wrote several articles that appeared in Disunion, including a piece about Chimborazo, the largest Civil War hospital in Virginia. This history of medicine article discusses the creation and staffing of the hospital, focusing in part on race and gender and how southern Civil War nursing differed from northern Civil War nursing.

My second novel is a retelling of Romeo and Juliet entitled Juliet’s Nurse, although the nurse is a wet-nurse, a woman hired to breastfeed. But again, writing about medical practices, particularly about pregnancy and childbirth, provided a way to make the era in which the novel is set (fourteenth-century Verona, Italy) real for readers. Even if you’ve forgotten most of the details of Shakespeare’s play, you might remember the line “A plague on both your houses,” which one character utters three times as he’s dying from a sword-fighting wound. Plague came to Italy in 1348, and within 2 years it killed 40% of the population. This devastating loss of life had huge effects on everything from marriage patterns to who could train for particular professions; in many ways, it contributed to the end of the medieval period and the beginning of the Renaissance. Imagining what it was like to live through such loss—and through the return to “normalcy” after the plague ran its course—became part of the way I explore how people enduring suffering, a major theme in the novel.

Of course, Romeo and Juliet is a play about suicide, which means that Juliet’s Nurse became a novel about surviving the loss of a child to suicide. After it was published, I wrote a creative nonfiction essay about authors and suicide, and particularly how writing about losing someone to suicide might be a way to resist one’s own suicidal impulse. When “All the Years Ahead: On Committing Literary Suicide” was published in The Millions, my friend Paul Pottinger, a physician on the faculty at the University of Washington, said he wished someone would write something like that for medical doctors. That was the first I learned of the epidemic of suicide (and depression, and burnout) among physicians.

Nearly a year later, Paul Kalanithi’s memoir When Breath Becomes Air was published. It recounts Kalanithi’s diagnosis with a rare advanced lung cancer, his treatment, and his final months of life–all of which happened when he was in his thirties, working as a neurosurgery resident. But when I read the book, I realized it also tells the story of another physician’s death: Kalanithi’s best friend in residency, who died by suicide. I ended up writing “The Hidden Dying of Doctors: What the Humanities Can Teach Medicine, and Why We All Need Medicine to Learn It” for the Los Angeles Review of Books. That was the first time I really thought of myself as “doing medical humanities.”

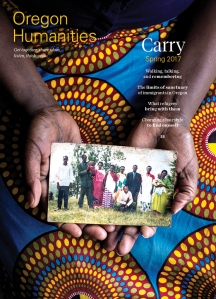

Since then, I’ve taught a class at the Portland Art Museum on how literature and visual art shapes our understanding of illness and the end of life. I’ve led humanities workshops at several medical conferences. I’ve spent a year as a Kienle Scholar in Medical Humanities at Penn State University. I wrote “When It Shifts,” a micro-memoir for Oregon Humanities magazine, about a sunny afternoon with a friend on hospice.

Recently, learning another friend, my poetry teacher and mentor Peter Sears, was at the end of his life, I began re-reading Peter’s work, and was amazed at how many of his poems were about illness or death or caretaking or, well, let’s just say “medical humanities.” That prompted me to reread poems I’d written, some years ago, and discover the same preponderance of themes. Books of poetry I taught years ago suddenly have new resonance for me, because I realize what they reveal about medical humanities. I reconnected with a friend from graduate school, only to discover he, too, has been drawn to this field. I’m revising a chapter for a book that Cambridge University Press will publish about film and television adaptations of Shakespeare’s King Lear, and discover that the television show I’m writing about uses Lear to explore what happens as a legendary Shakespearean actor dies of cancer. Or maybe it uses what happens when a legendary Shakespearean actor dies of cancer to explore Lear. (Turns out, Shakespeare is very relateable!)

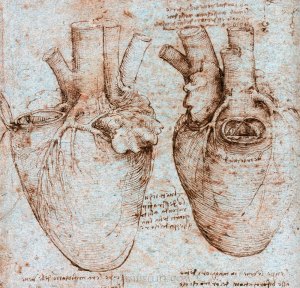

And Tuesday I begin teaching my new medical humanities seminar on the heart. Because it turns out, all of this “doing medical humanities” is heart work.

Then I asked what connections they could make from what we collectively observed about this painting and medical education/the practice of medicine. This gave everyone a chance to reflect on how relationships shape medical care, on what role intimacy plays in healing, on how concepts like foreground/background or light/shadow can serve as metaphors for medicine. Then we moved on to discussing Denise Levertov’s poem Talking to Grief. It was a risk to try to cover two works in such a short session, but I wanted participants to experience how talking about something as different as a painting or a poem could be equally helpful in talking about medicine. We finished by taking time to share thoughts about what impact sessions like this could have for medical students, for practitioners, and for patients and their families.

Then I asked what connections they could make from what we collectively observed about this painting and medical education/the practice of medicine. This gave everyone a chance to reflect on how relationships shape medical care, on what role intimacy plays in healing, on how concepts like foreground/background or light/shadow can serve as metaphors for medicine. Then we moved on to discussing Denise Levertov’s poem Talking to Grief. It was a risk to try to cover two works in such a short session, but I wanted participants to experience how talking about something as different as a painting or a poem could be equally helpful in talking about medicine. We finished by taking time to share thoughts about what impact sessions like this could have for medical students, for practitioners, and for patients and their families.